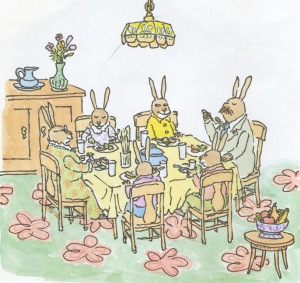

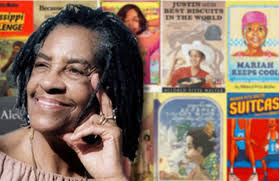

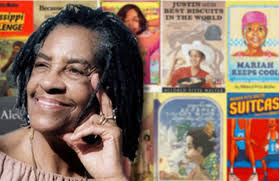

On Martin Luther King Day, I’m thinking about my friend, the children’s book author Mildred Pitts Walter.

In the late 1960’s when she was kindergarten teacher in Los Angeles and active in the Civil Rights struggle there, Mildred could not find books for children of color. When she challenged a representative of the local Ward Ritchie Press to find and publish black writers, he challenged her to become one, insisting that she write for their list. This led to her first book, LILLIE OF WATTS, published in 1969.

That same year two school librarians, Glendon Greer and Mabel McKissack founded the Coretta Scott King Award at an American Library Association convention. The recognition provided by this award, which has grown in stature with each passing year, provides enormous encouragement and support to black authors and illustrators. It has played a large part in increasing the number of books published that feature young black people.

I began to work with Mildred in 1984 when I edited TY’S ONE MAN BAND, a picture book that drew on memories of a peg-legged man who sometimes appeared in her Louisiana community and enlivened the day with music. From the start, I knew that Mildred was passionate about the power of books to change children’s lives, and I couldn’t wait to see what she’d do next.

In 1987 her JUSTIN AND THE BEST BISCUITS IN THE WORLD was a Coretta Scott King Award winner, and it is perhaps her most endearing and enduring work. The beautifully evocative TROUBLE’S CHILD is the most autobiographical. But the novel that that made the deepest impression on me is THE GIRL ON THE OUTSIDE.

THE GIRL ON THE OUTSIDE is told from two points of view: Eva is a black girl chosen to integrate a high school in Little Rock. Sophia is the white girl who finds the courage not join the mob who is jeering and spitting at her. The understanding and love brought to the portrayal of the white girl’s emotions was sobering. Later, Mildred undertook the painful retelling of events in Mississippi during the Civil Rights era. MISSISSIPPI CHALLENGE won the Christopher Award for Non-fiction, but it had required intense research and reliving tragedy upon tragedy. How, I wondered, can she even be talking to me?

Happily, from our first meeting to the present day, the conversation has continued and the friendship has grown. And, at 92, Mildred continues to actively work for reconciliation, the healing of the continuing harm slavery and guilt about slavery have brought to the nation.

She has said, “I have tried to show the dynamics of choice, courage, and change in my books so that white readers can, through the experiences of black characters, appreciate differences and become thoughtful; and so that black readers through those experiences, can not only become thoughtful, but aware of themselves as well.”

And she has just written:

Love is the gleam of light in the eye.

It is a warm touch in the silent night;

A feeling that every male is my brother

Every female my sister.

Love is dignity shown to all that is created;

The firm non-violent action for peace,

Justice and equality for all where at

Its center stands the principle of LOVE!